Art is the ingenuity of the message, and craft is the clarity of its expression. I've always tried to be more of an artist than a craftsman. The reason is simple. I'm lazy. Rather than admit that, though, what I'm more likely to preach at you is that art, or rather, Art, "should not be corrupted by technical details. Purity and honesty of vision is above parameters." Honestly, though, I'm full of crap. You shouldn't believe me when my voice takes on that transcendent tone. The truth is that art is never fully actualized, never sublime, until its practitioner is sufficiently trained in her craft. Elegance, balance, tone, voice—all of these expressions require skill to be effectively communicated. Craft, however, rarely needs art.

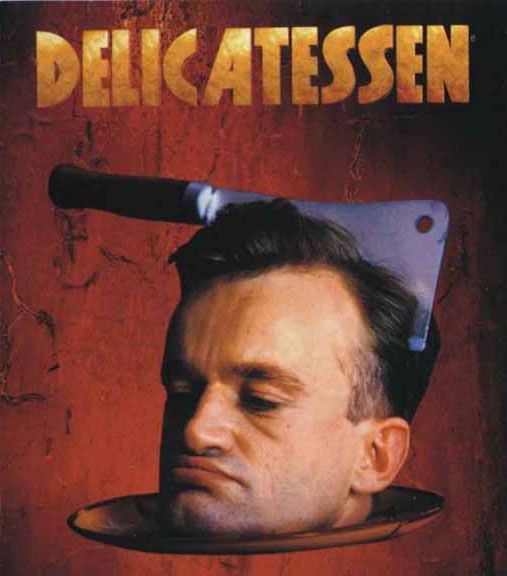

Consider, say, any film by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. He's the madman who made the beautiful movies Delicatessen, City of Lost Children, and Amélie, just to name a few. His movies are brilliant and original. Every aspect of the work conveys an overall style discernable at a glance. That is his stamp; his craft. The artistry comes from another place. His stories are imaginative and characters surprising. There is always something unusual but charming to his films. Delicatessen, for example, is a post-apocalyptic and romantic story where society functions with an economy of old corn kernels and stale beans while hapless renters of a particular flat tend to find themselves in the butcher's shop, but on the wrong side of the display case. This creepy story of cannibalism and love is disarmingly cute. The lighting, the costumes, the editing are the craft. The dissonance and its resolution is the art. This point is further made on the distinctive face of Dominique Pinon, the lead actor in a cast of mildly distorted individuals. Jeunet has a liking for exaggerated physical features on a person, like a particularly broad mouth, long nose, or stout body; even better if all three are on one guy. What might appear off-putting in any other context becomes adorable when Jeunet creates the scene for it.

Consider, say, any film by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. He's the madman who made the beautiful movies Delicatessen, City of Lost Children, and Amélie, just to name a few. His movies are brilliant and original. Every aspect of the work conveys an overall style discernable at a glance. That is his stamp; his craft. The artistry comes from another place. His stories are imaginative and characters surprising. There is always something unusual but charming to his films. Delicatessen, for example, is a post-apocalyptic and romantic story where society functions with an economy of old corn kernels and stale beans while hapless renters of a particular flat tend to find themselves in the butcher's shop, but on the wrong side of the display case. This creepy story of cannibalism and love is disarmingly cute. The lighting, the costumes, the editing are the craft. The dissonance and its resolution is the art. This point is further made on the distinctive face of Dominique Pinon, the lead actor in a cast of mildly distorted individuals. Jeunet has a liking for exaggerated physical features on a person, like a particularly broad mouth, long nose, or stout body; even better if all three are on one guy. What might appear off-putting in any other context becomes adorable when Jeunet creates the scene for it.My point is that a hallmark of artistry is that the viewer is taken by surprise. This isn't to say that jumping out and scaring you is necessarily artistic, of course. It's not quite that simple. What I mean is that oftentimes in art, elements which shouldn't work together combine to make something better than the individual parts would suggest. This can be easily seen by the efforts of certain filmmakers, but the same is true for great musicians, painters, dancers, etc. Bach is artistic because of the surprising ways that he interprets a theme. He, and Jeunet, and Escher, and all the rest of the people I consider master artists, are also master craftsmen. They have to be. Having a great idea is one thing, but if it's packaged poorly and lacks tireless attention to detail, then it's only a good idea poorly executed.

Jeunet's films work not because he has great ideas, but because he is technically adept. Perhaps his subjects are bizarre, his color choices unique, and his camera angles surprising, but they are always chosen with precision. For that reason the story is elevated from interesting to fascinating. We are sucked into his world, and we don't really mind that we may end up on the dinner menu.

To put it simply, craft equals technical ability. It is learned by rote and developed through practice. It is the instrument used to communicate a message to as many people as possible. Let's compare it to quilting. If you can stitch a good one, and you can keep a person warm, that is craft. If you have a good eye for colors that work well together, then you have made a warm covering that's also pleasant to look at. This is, well, crafty. If you can do all of that, but make your high-quality quilt in the shape of a giraffe, that is art. On the other hand, cut a ratty old piece of denim into the vague silhouette of an animal, and it may be art, but who cares?

This gets to the proof of my argument that art needs craft but craft does not need art. Most cinema, as most "art", is simply not good. But hundreds of thousands of people line up to see new releases of the same old stories every weekend. The reason is that if technical skill is in place then whatever Tom Cruise happens to blow up will make us feel good. That's his job. But a truly creative film with no technical expertise will not make us feel anything very deeply. Frustration, maybe—or indignation, but not much else. We will either decide to hate the attempt for its conceit, or love for it for its intellectual challenge. Either way, we are not exactly moved.

As I said, craft is what makes a message clear. Even if that message is the same thing I've heard thousands of times. The phrase, "I love you," has meaning so long as I believe you when you say it. But if you express your feelings in German, I won't have any idea what you're talking about, and I'll probably think you're angry at me. Great film, like all great Art, requires an original perspective in a comprehensible format. It requires Art and Craft. -dg

This is great. In ad school one of my professors was doing the whole "perspiration vs. inspiration" talk, and this kind of reminded me of that. And this is why I like pasta scoops shaped like dinosaurs.

ReplyDeleteI love you!

So I'm guessing you nailed it in the first sentence. There's no defining art really. It's the whole tree falling in the forest thing; partly it serves the person doing it, and partly it serves the people receiving. Sometimes it does only one of those things (Last Thursday; Thomas Kinkade). Speaking personally, though, I rarely enjoy art without the craft. I want to see some muscle and chops.

ReplyDeleteEven if I like something, I tend to think less of it if it looks like something I could have done.

And you, Murr, nailed it in the last sentence.

ReplyDelete